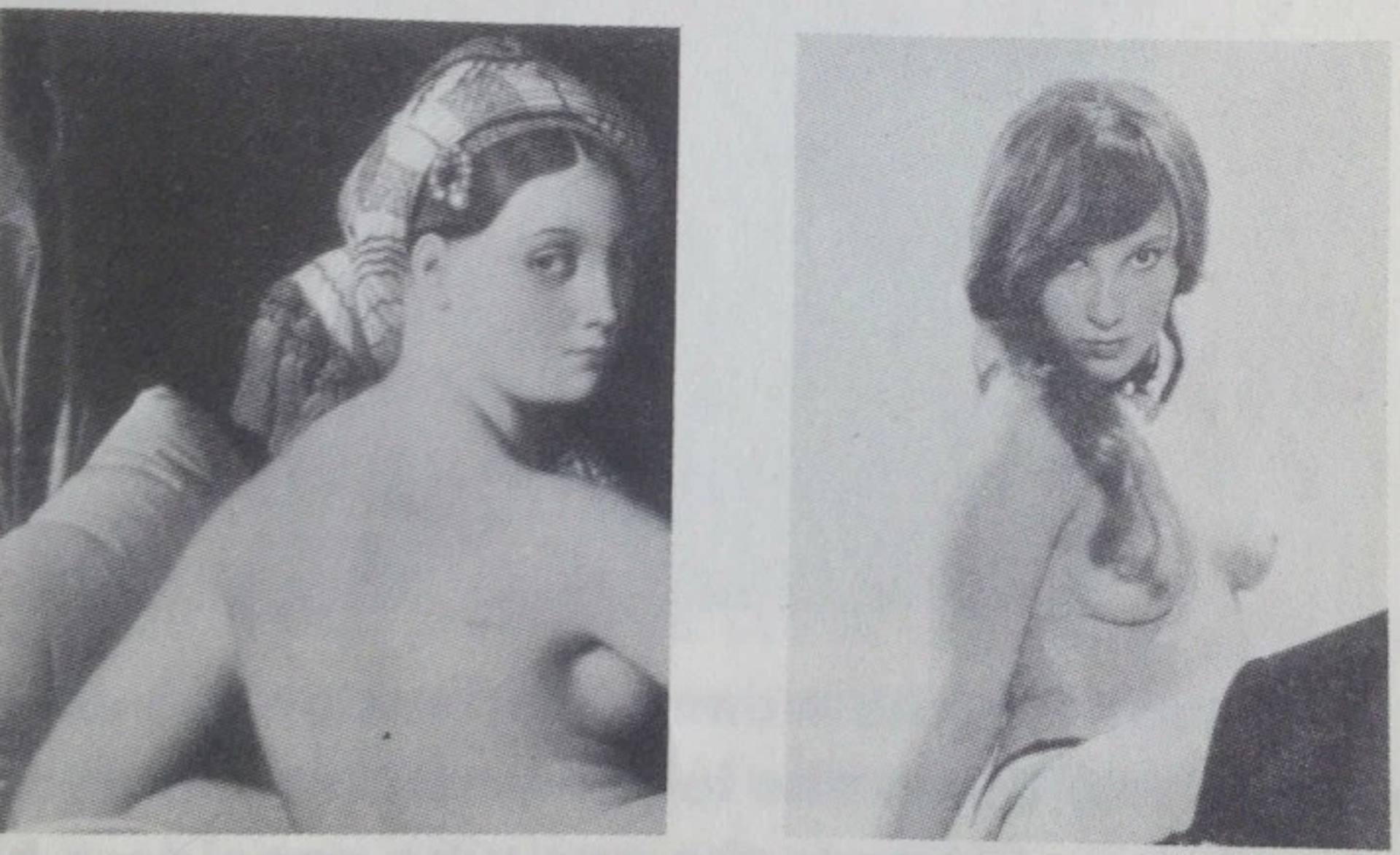

However, McCormack’s analysis snags on pop culture. “Or do we quicken with the thrill of conquering her?” A stellar section called “Monstrous Women” asks if “Medusa was originally a Black African deity from Libya … a question that classics scholars have wanted to shrug off and undermine.” The chapter “Maidens and Dead Damsels” implores us to query our own responses to Titian’s painting “The Rape of Europa.” “Do we share Europa’s desperation?” she writes. Venus, befittingly the first, is especially engrossing, her range of poses encompassing the celestial (“ Venus Coelistis was thought of as a pure and unearthly body of a woman which stimulated thoughts about divine love and the beauty of the soul”) and the earthly (“Venus Vulgaria was the earthbound Venus associated with fertility, sex, procreation and the beauty of the living world”). Such archetypical figures, branded into the collective consciousness, order the book’s chapters. In the painting, men talk a lot.” Fleeing the stranger’s “tedious ‘mansplaining,’” McCormack finds no refuge around the corner, where she sees hanging another Renaissance painting of “a woman on the ground with her throat pierced, oozing blood from her jugular and with a deep gash on her forearm, her wrists already hooked with rigor mortis her high round breasts and gently curving stomach egregiously exposed.” On a visit to the National Gallery in London, her infant child bouncing on her hip, McCormack is approached by a male stranger, who tells her, “I wouldn’t look too deeply into the symbolism in this one.” She is gazing at “The Story of Griselda,” a 15th-century triptych whose central focus is “a longhaired woman surrounded by a lot of men in tights and a menagerie of animals. “Women in the Picture” opens with a rather pedestrian encounter from the author’s own experience. Her more polemical follow-up is as incisive and provocative on the subject of motherhood as was “Matrescence and Maternality,” a two-part exhibition she guest curated at Richard Saltoun Gallery in London in 20. This is the author’s second book after 2019’s “The Art of Looking Up,” a survey of classical ceiling art, from the azul tiles of the Iranian Imam Mosque to the Medici frescoes in Italy. Yes, McCormack says, women sometimes peer but at least within the canon, they are mostly peered at. McCormack continues these lines of inquiry, contemplating the various familiar, circumscribed shapes the female figure has been forced to take on the canvas: dead, floating Ophelias endless sacrosanct Madonnas denuded women of leisure persecuted wives coquettish nymphs and wrathful deities - fetishized and tragic all.

“the castration complex”) and the film theorist Laura Mulvey, who wrote in 1975 that “in a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female.”

Women watch themselves being looked at”), Sigmund Freud (cf. She’s not the first: The female self-image has long been fodder for critics like John Berger (“Men look at women. In “Women in the Picture,” the author, scholar and art curator Catherine McCormack confronts the inexhaustible matter of women as objects of attention, in Western visual art and elsewhere.

WOMEN IN THE PICTURE What Culture Does With Female Bodies By Catherine McCormack

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)